Your User Agent is:

Your IP Address is:

103.82.80.117

103.82.80.117Browser Information:

| JavaScript Enabled: | Yes |

|---|---|

| Cookies Enabled: | Yes |

| Device Pixel Ratio: | 1 |

| Screen Resolution: | 1366px x 768px |

| Browser Window Size: | 1349 px x 638 px |

| Local Time: | 4:42 pm |

| Time Zone: | -5.5 hours |

User agents are unique to every visitor on the web. They reveal a catalogue of technical data about the device and software that the visitor is using. Armed with this information, you can develop richer and more dynamic websites that deliver different experiences based on the user agent that’s visiting.

User agents are also critical in controlling search engine robots using the robots.txt file on your server. But they dont function perfectly in every situation, and the information in a user agent string can be faked.

In order to leverage this information, you need to understand the component parts of a user agent string, and consider also the potential risks of using this method to deliver content.

What is a User Agent?

Everyone that is browsing the web right now has a user agent. It’s the software that acts as the bridge between you, the user, and the internet. It’s easiest to understand user agents if we backtrack and look at the evolution of the web, so we can understand the benefits of user agents.

When the internet was a text-based system, right back at the beginning of its use, users had to type commands to navigate and send messages. Now, we have browsers to do that for us. We simply point and click, and the browser is acting as our “agent,” turning our actions into commands.

When your browser (or similar device) loads a website, it identifies itself as an agent when it retrieves the content you’ve requested. Along with that user agent identification, the browser sends a host of information about the device and network that it’s on. This is a really set of data for web developers, since it allows them to customize the experience depending on the user agent that’s loaded the page.

User Agent Types

Browsers are a straightforward example of a user agent, but other tools can act as agents. Crucially, not all user agents are controlled or instructed by humans, in real time. Search engine crawlers are a good example of a user agent that is (largely) automated — a robot that trawls the web without a user at the helm.

Here’s a list of some of the user agents you’ll encounter:

- Browsers: Including Internet Explorer, Firefox, Safari, Chrome, Edge, BlackBerry, Opera, Minimo, Beonex and the AOL browser.

- Crawlers: Google, Google Images, Yahoo! Slurp, and hundreds more.

- Consoles: PlayStation 3, Wii, PlayStation Portable and Bunjalloo — the Nintendo DS’ built-in browser.

- Legacy operating systems (for example, AmigaVoyager).

- Offline browsers and similar (for example, Wget and Offline Explorer).

- Link checkers (for example, W3C-checklink).

- Plus a whole range of feed readers, validators, cloud platforms, media players, email libraries, and scripts.

Reading HTTP User Agent Strings

Once the user agent has identified itself to the web server, a process called content negotiation can begin. This allows the website to serve different versions of itself, based on the user agent string. The agent passes its ID card over to the server, and the server then negotiates a combination of suitable files, scripts, and media.

In the early days of the web, user agents were used to distinguish Mosaic from Mozilla, since Mosaic did not support frames, while Mozilla did.

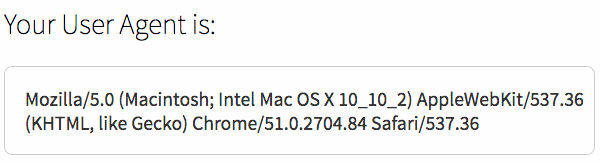

To look at a user agent string in more detail, take a look at this example user agent string, as generated by the WhoIsHostingThis User Agent Tool. Your results will be unique to your computer, device and network, but here one from a computer we have in the office:

Breaking the example down, we get the following information:

- The user agent application is Mozilla version 5.0, or a piece of software compatible with it.

- The operating system is OS X version 10.2.2 (and is running on a Mac).

- The client is Chrome version 51.0.2704.84.

- The client is based on Safari version 537.36.

- The engine responsible for displaying content on this device is AppleWebKit version 537.36 (and KHTML, an open source layout engine, is present too).

Dissecting user agent strings can be tricky, since there is no standard format. But there are guides and analytics tools all over the web that can help. For most designers, the application, version and engine are likely to be key.

Note that a huge part of the user agent string is concerned with compatibility. That’s because Internet Explorer originally had to declare itself to be Mozilla compatible in order to receive content with frames.

In practice, the majority of browsers now declare themselves to be Mozilla compatible to ensure that they can access all of the content on the web.

Content Negotiation

So: the user agent string is a little muddled. But it’s still useful. What can we do with it?

We can:

- Check the capabilities of the browser or device, and load different CSS based on the outcome;

- Deliver custom JavaScript to one device compared with another;

- Send an entirely different page layout to a phone, compared to a desktop computer;

- Automatically send the correct translation of a document, based on the user agent language preference;

- Push special offers to particular people, based on their device type or other factors;

- Gather statistics about visitors to inform our web design and content production process, or simply measure who’s hitting our site, and from which referral sources.

Overall, we can empower our scripts to make the best choice for our visitor, based on their user agent. And we can feed that data back into a cycle of continuous improvement, analytics and other processes, like conversion optimization.

User Agents and Robots.txt

The robots.txt file is a file on your web server that controls how some user agents behave. In the majority of cases, we use robots.txt to tell search engine crawlers — or “robots” — what to do.

As we mentioned in the introduction, search engine crawlers are a very specific type of user agent. The information in the robots.txt file applies only to crawlers, and it’s up to the crawlers to interpret them as we intend.

Let’s look at some examples.

If we wanted to ban all crawlers from visiting a website, we’d create a text file called robots.txt, place it in the top level (web accessible) directory on our server, and add the following text:

|

1 2 3 4 |

User-agent: * Disallow: / |

- The asterisk (*) means we’re issuing the instruction to all search engine crawlers.

- The forward slash (/) means that we’re denying them access to everything within our web directory and its subfolders.

- The robots.txt file must have every disallow statement on a separate line.

- The instruction will not work if the file contains any blank lines.

If you want your site to be indexed in search engines, adding the code above would be a bad idea. To stop robots from getting to the contents of one directory, but allowing access to everything else, we could also do something like this:

|

1 2 3 4 |

User-agent: * Disallow: /my-video/ |

To stop Google from indexing the page /bad-google.htm, but allow all other robots to see it:

|

1 2 3 4 |

User-agent: Google Disallow: /bad-google.htm |

Or, to stop Google Image Search from indexing photos anywhere on the site:

|

1 2 3 4 |

User-agent: Googlebot-Image Disallow: / |

In theory, all crawlers should respect the preferences you’ve placed in the robots.txt file, but there will always be malicious attempts to misuse user agents to spread malware and scan sites for weaknesses. So it’s a good idea to have one, with the caveat that it may not always be recognised and used as you want it to.

User Agent Spoofing

Using user agent strings to control how a site behaves is not completely a fool-proof method, because some user agents are not what they seem.

It’s possible to send a fake user agent, a process known as “spoofing.” This can be used for innocent purposes — like usability, or testing. It can also be used to manipulate content or impersonate another device maliciously.

Why does this matter? Because:

- On the positive side, many browsers can identify themselves as other browsers, for compatibility or development purposes. The browser on Android devices is set to spoof Safari to avoid problems when loading content, and the Dolphin browser on Android has a very useful desktop spoofing mode.

- On the negative side, spoofing can be used maliciously. For example, a script could spoof a regular web browser in order to clone content without being detected as a malicious, automated tool. A robot could also impersonate a different user agent to get around robots.txt restrictions, or to disguise repeated visits.

If you see strange visitor behavior, and you suspect it’s a spoofed user agent or malicious crawler, the best thing to do is to block the IP address to be absolutely sure it can’t visit your site.

Programming with User Agents Information

This guide is intended to be a very brief reference to the different methods you can use. For precise implementation see the specific usage guidelines in the language’s documentation.

PHP

To retrieve the current visitor’s user agent string, use:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

<?php echo $_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT'] ?> |

To display information about the browser, use:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

<?php $browser = get_browser(null, true); print_r($browser); ?> |

Perl

The official Perl documentation recommends retrieving the user agent string, and returning that as an object:

|

1 2 3 |

$ua = Parse::HTTP::UserAgent->new( $str, { extended => 0 } ); |

.NET

User agent data is stored in the HttpProductInfoHeaderValueCollection class.

Java

Download the UA Detector open source library to parse the user agent. UA Detector can identify around 750 different user agents, including almost 200 different browsers.

JavaScript

User agent information is stored in the userAgent property. This saves the user agent string in a variable and then displays it in an alert box:

|

1 2 3 4 |

userAgentString = navigator.userAgent; alert(userAgentString); |

Summary

The user agent is not a failsafe way to identify a device, browser or user. It can be spoofed, and a user can choose to hide it. But in the vast majority of cases, the user agent is a very useful way to see the mechanics of the device that’s accessing a site. We can use the data within the user agent string to create more effective websites and gather statistics about visitor trends. We can also use robots.txt to limit what certain user agents see.

Further Reading and Resources

We have more guides, tutorials, and infogragphics related to coding and development:

- Robots.txt Ultimate Guide: learn all about the robots.txt file and how to become an expert on it.

- Sender ID Introduction and Resources: spoofing is something more common in email. This article discusses one technology for protecting our email.

- The History of Search Engines: this is a fascinating article that takes you through the history of internet search engines. It’s taken us over five decades to get here!